Introduction

The Battle of Gettysburg stands as one of the most iconic and significant clashes of the American Civil War. Fought over three tumultuous days from July 1 to July 3, 1863, in and around the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, this engagement altered the course of the war. It was here that Union and Confederate forces met in a struggle that would come to symbolize both the high cost of conflict and the resilience of a nation in turmoil.

More than 150 years later, people still ask: Who won the Battle of Gettysburg? Why is it so often referred to as the war’s turning point? Why was the Battle of Gettysburg important, and how did it come to be etched so firmly into the American national memory? These questions and more continue to fascinate historians, students, and casual learners alike.

In this comprehensive account, we will explore all the essential details of the Battle of Gettysburg, weaving together key facts, daily developments, and the human drama that unfolded under the summer sun of 1863. By delving into the strategies, the leadership, the casualties, and the historical significance, this article aims to provide a succinct yet richly textured portrait of one of American history’s most pivotal events.

Background: Prelude to the Battle

By the summer of 1863, the American Civil War had already taken a terrible toll on both the Union and the Confederacy. Major battles at Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville had left thousands dead or wounded. The Confederacy, led by General Robert E. Lee, had achieved noteworthy victories in Virginia. However, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was in desperate need of supplies and a decisive blow that might force the North to sue for peace.

Determined to shift the war’s focus away from Virginia, Lee set his sights on the North. His plan involved moving his troops across the Potomac River and into Pennsylvania, hoping to disrupt Northern morale and perhaps even threaten major cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Washington, D.C. This gamble would ideally pressure the Union into political negotiations or, at the very least, demonstrate that the Confederacy was strong enough to operate on Union soil.

Meanwhile, President Abraham Lincoln and the Union high command were under immense pressure. With increasing casualties and a public weary of war, the Union’s leadership was desperate for a victory that could restore faith in the cause. Major General George G. Meade had just recently assumed command of the Army of the Potomac, replacing General Joseph Hooker. Despite the leadership shake-up, the Union Army was resolute in its mission to thwart Lee’s invasion. The stage was set for a confrontation that neither side could fully anticipate.

Day One (July 1, 1863): The Clash Begins

Early Morning Maneuvers

On July 1, Confederate forces under General Henry Heth approached Gettysburg from the northwest, largely unaware of the Union cavalry presence commanded by Brigadier General John Buford. Buford recognized the high ground around the town—particularly the ridges and hills to the south and east—and understood their critical defensive value. Determined to hold the advantageous terrain until Union infantry reinforcements could arrive, Buford’s cavalrymen dismounted and prepared to make a stand.

Despite being outnumbered early in the day, the Union cavalry used their breech-loading carbines effectively, slowing down Confederate advancements on the outskirts of town. Meanwhile, additional Confederate divisions advanced from the north and west, creating pressure on Union positions.

Expanding Engagement

By midday, Union infantry brigades led by Major General John F. Reynolds arrived to bolster Buford’s defense. Tragically, Reynolds was killed in action, a severe blow to the Union leadership just as the battle was unfolding. Still, the Union forces managed to maintain a reasonably coherent defensive line. Ultimately, as the Confederates continued their relentless pressure, the Union troops were compelled to retreat through the town of Gettysburg, pulling back to higher terrain to the south along Cemetery Hill.

Late in the day, the arrival of more Union corps helped stabilize the line, consolidating vital high ground positions at Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Ridge. Although Day One ended in a Confederate tactical victory in terms of terrain gained (the Union had pulled back from the town), the ultimate prize—control of the crucial high ground—remained in Union hands. Both armies then prepared for what was to come, amassing tens of thousands of soldiers.

Day Two (July 2, 1863): Key Engagements and Maneuvers

Shifting Strategies

By the morning of July 2, nearly 65,000 Confederate soldiers under General Lee had converged near Gettysburg, while about 85,000 Union troops under Major General Meade took up defensive positions along the heights and ridges south of town. Confederate leadership recognized that the Union had strong defensive terrain, but General Lee believed that another aggressive push could deliver a decisive victory.

Lee divided his forces to attack both the left and right flanks of the Union line. Lieutenant General James Longstreet was tasked with assaulting the Union left at places like the Peach Orchard, Devil’s Den, and the rugged terrain known as Little Round Top. Meanwhile, Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell aimed at the Union right flank on Culp’s Hill.

Critical Moments at Little Round Top

One of the most dramatic episodes of the entire battle took place at Little Round Top, a rocky hill at the extreme left of the Union line. The 20th Maine Regiment, led by Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, was positioned at the far left flank. Recognizing that a Confederate breakthrough here could roll up the entire Union line, Chamberlain’s men fought fiercely to maintain their hold.

After multiple Confederate charges up the slope, the 20th Maine found its ammunition dangerously low. In a desperate maneuver, Chamberlain ordered a downhill bayonet charge that surprised and repelled the attacking Confederate forces. This successful defense proved essential in preserving the Union flank, preventing what could have been a catastrophic envelopment.

Heavy Fighting Across the Line

Day Two also saw intense combat at the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, and Cemetery Ridge, with both sides suffering staggering casualties. Though the Confederates made progress in some areas, they failed to break the Union line in a decisive way. By nightfall, the Union defensive positions largely held, and Meade’s forces braced for what they suspected would be another major Confederate assault.

Day Three (July 3, 1863): The Pivotal Moment

Artillery Barrage

On the morning of July 3, the Union regained control of Culp’s Hill after intense early firefights. Over on the Confederate side, Lee resolved to strike at the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. This decision led to one of the most famous and fateful events of the American Civil War: Pickett’s Charge.

Prior to the infantry assault, Confederate artillery opened up a massive barrage meant to weaken Union defenses. The thunder of cannons echoed across the battlefield for nearly two hours. While impressive, the bombardment did not achieve its intended effect of disrupting the Union line. Union artillerymen conserved their fire so as not to reveal their positions until the Confederate infantry began to advance.

Pickett’s Charge

Under the overall command of Longstreet, roughly 12,000 Confederate soldiers, including the division of General George Pickett, stepped out of the woods and began a nearly one-mile march across open fields under heavy Union artillery and rifle fire. The charge was directed at a copse of trees on Cemetery Ridge, a point later referred to as the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy.”

As the Confederate troops approached, Union defenders unleashed devastating volleys, shredding the columns. Despite valiant efforts, the Confederates could not break through. Large segments of their lines were decimated, with casualties soaring. Many Confederate soldiers who survived the initial onslaught either surrendered or retreated. The failure of Pickett’s Charge effectively marked the end of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Aftermath of Day Three

By the evening of July 3, Lee’s second invasion of the North had come to a standstill. Recognizing that his army was too battered to launch another assault, Lee prepared to withdraw. Heavy rain complicated his retreat on July 4, but the remaining Confederate forces managed to slip back across the Potomac River in the days that followed. The Union Army, exhausted and wounded itself, did not mount a full pursuit.

Who Won the Battle of Gettysburg?

In the simplest terms, the Union emerged victorious at Gettysburg. The Confederate Army, though formidable, could not maintain its presence on Northern soil or destroy the Army of the Potomac. The Union’s defensive positioning, combined with effective leadership from Meade and key subordinates, allowed them to repel the Confederate assaults. This Union victory is widely seen as a major turning point in the war, boosting Northern morale and weakening the Confederacy both militarily and psychologically.

Battle of Gettysburg Summary

For three days, two massive armies clashed in a corner of Pennsylvania farmland, culminating in one of the most ferocious battles in American history. Day One saw the Confederates push Union forces back through Gettysburg, but the Union retained control of the vital high ground. Day Two witnessed fierce fighting along the Union flanks, most notably the heroic stand at Little Round Top. Finally, Day Three ended in the disastrous Pickett’s Charge, which decimated Confederate hopes for a breakthrough.

When the smoke cleared, the Union had forced General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw. While the war would continue for almost two more years, the tide had decisively turned in favor of the North. Gettysburg, together with the Union capture of Vicksburg in the Western Theater on July 4, 1863, represented a dual blow from which the Confederacy never fully recovered.

Why Was the Battle of Gettysburg Important?

The importance of the Battle of Gettysburg goes far beyond the immediate tactical outcomes:

- Moral Boost for the Union

The victory at Gettysburg came at a critical moment. The Union had experienced multiple setbacks, and public support for the war was wavering. News of a significant triumph on Northern soil rejuvenated both civilian morale and military confidence. - Turning Point in the War

Although debates continue among historians about the single turning point of the Civil War, many point to Gettysburg because it halted Lee’s momentum and ended his hopes of a successful invasion of the North. Confederate forces would subsequently adopt a more defensive posture, rarely venturing far into Union territory again. - Symbolic Resonance

Gettysburg became a powerful symbol of unity and sacrifice, especially following President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in November 1863. In just a few short paragraphs, Lincoln redefined the war effort as a struggle not just for Union victory, but for the principle of human equality and the fulfillment of America’s founding ideals. - Strategic Advantage

By defeating Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, the Union gained a significant strategic edge. The Confederates lost irreplaceable men and resources, weakening their ability to go on the offensive. This shift in strategic momentum set the stage for future Union successes.

Battle of Gettysburg Casualties

The sheer scale of destruction at Gettysburg continues to astonish modern observers. Although exact numbers vary by source, it is generally accepted that total casualties exceeded 50,000. This figure encompasses killed, wounded, captured, or missing soldiers. The Union Army suffered around 23,000 casualties, while the Confederates lost an estimated 28,000 men. These staggering numbers underscored the brutal nature of the conflict, shocking both North and South.

Civil War-era medical knowledge and technology were limited, meaning that many of the wounded did not receive adequate treatment. Makeshift field hospitals were overwhelmed, and Gettysburg’s small population was unprepared for the influx of thousands of injured soldiers. The massive casualties and their lingering impact on the town became a somber reminder of war’s grim toll.

Key Generals in the Battle of Gettysburg

Union Generals

- Major General George G. Meade

Appointed to command the Army of the Potomac just days before the battle, Meade navigated the chaotic opening events and orchestrated the Union defense. His leadership is often praised for its effective use of terrain and overall coordination. - Major General John F. Reynolds

Reynolds was among the finest commanders in the Union Army but was tragically killed early on Day One. His death marked a critical loss for the Union, but his rapid deployment of forces in the initial hours helped secure the high ground. - Major General Winfield Scott Hancock

Known as the “Superb,” Hancock was instrumental in organizing Union defenses on Cemetery Ridge. He later coordinated much of the response to Pickett’s Charge, sustaining a severe wound in the process. - Brigadier General John Buford

Buford’s cavalry division played a pivotal role in delaying the Confederate advance on July 1, allowing Union reinforcements to occupy Cemetery Hill and other strategic locations. - Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

Although not a general at the time, Chamberlain’s leadership of the 20th Maine at Little Round Top stands out as one of the battle’s legendary moments.

Confederate Generals

- General Robert E. Lee

Commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee brought his reputation for battlefield brilliance to Pennsylvania. Despite early successes, his decision to attack the Union center on Day Three proved costly. - Lieutenant General James Longstreet

Lee’s “Old War Horse,” Longstreet was a capable corps commander but is sometimes portrayed as reluctant to carry out Lee’s orders on Day Two and Day Three. His post-war writings spurred debate on whether he advocated for a more defensive strategy at Gettysburg. - Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell

Ewell commanded the Confederate Second Corps, tasked with attacking the Union right flank. A contentious topic is whether Ewell missed an opportunity to seize Cemetery Hill on the first day, potentially altering the entire battle’s outcome. - Major General George Pickett

Known primarily for leading the ill-fated Pickett’s Charge on Day Three, Pickett’s division faced catastrophic losses on the open fields of Gettysburg.

How Long Was the Battle of Gettysburg?

The Battle of Gettysburg lasted three days, from July 1 through July 3, 1863. While this might seem short compared to modern multi-week or even multi-month operations, the intensity of the fighting was extraordinary. In just three days, tens of thousands of casualties were inflicted, and the battlefield evolved rapidly from farmland to a chaotic expanse filled with fortifications, hastily dug trenches, and the grim realities of 19th-century combat.

Though the official engagement ended on July 3, the aftermath stretched into weeks and months, as wounded soldiers remained in makeshift hospitals, and townspeople struggled to care for the living and bury the dead. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863—over four months later—helped mark the ground as a national cemetery, adding a solemn final chapter to the costliest battle in American history in terms of total casualties sustained over such a short period.

Battle of Gettysburg Facts

- Date: July 1–3, 1863

- Location: Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

- Belligerents: Union Army of the Potomac vs. Confederate Army of Northern Virginia

- Union Commander: Major General George G. Meade

- Confederate Commander: General Robert E. Lee

- Outcome: Union victory

- Casualties: Estimated 51,000 total (Union ~23,000; Confederate ~28,000)

- Significance: Stopped the Confederate invasion of the North and became a turning point in the Civil War

These essential facts provide a quick snapshot of why the battle continues to loom large in discussions of American history. Few conflicts before or since have matched Gettysburg in scale and symbolic weight.

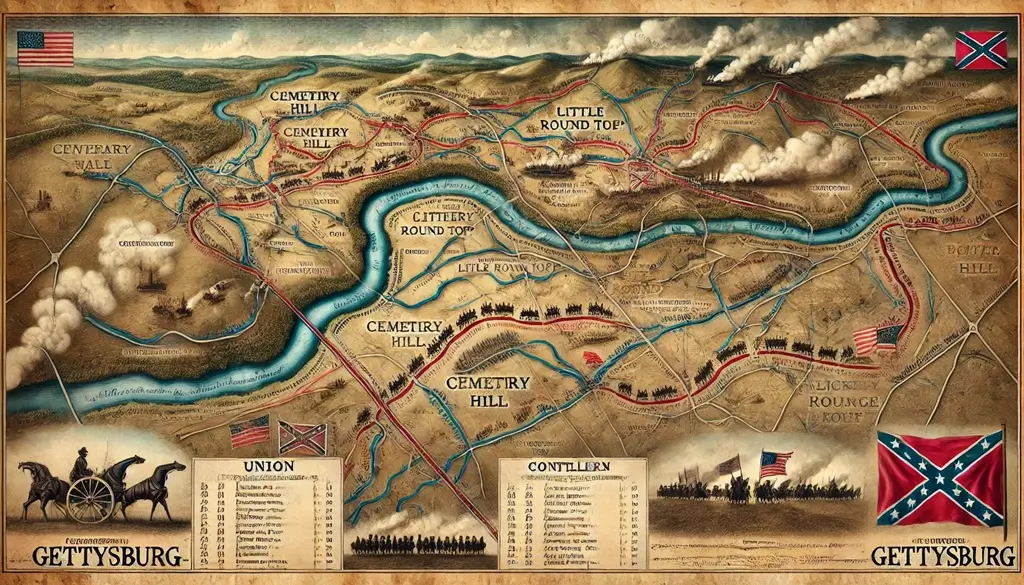

Battle of Gettysburg Map

The battlefield at Gettysburg stretched across rolling hills, ridges, and farmland near the town. Key topographical features include Seminary Ridge to the west, Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge in the center, and Culp’s Hill and Little Round Top on the Union right and left flanks, respectively.

While a visual Battle of Gettysburg map reveals how the terrain shaped the outcome, here are some crucial geographical notes:

- Town of Gettysburg: Strategically located at the crossroads of several major roads. The clash began just northwest of town and eventually encompassed the town proper and surrounding areas.

- McPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge: Key early positions for the Union cavalry and the subsequent Confederate approach on Day One.

- Cemetery Ridge and Cemetery Hill: Formed the central stronghold of the Union defensive line, running roughly north-south.

- Little Round Top: A rocky elevation at the extreme left of the Union line. This position was nearly overrun on Day Two but was famously held by Union forces.

- Pickett’s Charge: The infamous Confederate assault on July 3 commenced from Seminary Ridge, crossing approximately one mile of open farmland before reaching the Union line on Cemetery Ridge.

Even a rudimentary map highlights how the Union Army’s occupation of higher ground provided a defensive advantage. These natural barriers, coupled with interior lines that allowed for quick movement of reinforcements, presented Lee with a formidable challenge.

Conclusion

The Battle of Gettysburg remains a defining moment in American history, not merely because of its staggering casualty figures or the intensity of the fighting, but because it signaled a turning point in the Civil War’s narrative. Had the Confederate Army emerged victorious, the course of the war—and perhaps even the shape of the nation—might have been dramatically altered.

For three days in July 1863, the fate of a nation hung in the balance. Through the actions of leaders like Meade, Lee, Longstreet, Chamberlain, and Reynolds—along with the bravery of countless soldiers on both sides—the small Pennsylvanian town of Gettysburg became synonymous with courage, sacrifice, and the high cost of civil strife.

From the vantage point of history, the battle’s outcome sent a clear signal that the Union could withstand Confederate offensives and would eventually triumph. It bolstered Northern morale at a time of war-weariness and left the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia depleted in manpower and momentum. When Lincoln later delivered the Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863, he did more than dedicate a cemetery: he reaffirmed the principles of liberty and equality that the war—and especially the sacrifice at Gettysburg—had come to represent.

Today, Gettysburg National Military Park preserves much of the battlefield, allowing visitors to walk the very ridges, hills, and fields where pivotal actions took place. Historians and enthusiasts continue to analyze the conflict’s tactics, leadership decisions, and broader implications, and questions like “Who won the Battle of Gettysburg?”, “Why was the Battle of Gettysburg important?”, and “How long was the Battle of Gettysburg?” remain vital to understanding the Civil War. Though brief in duration, the events of July 1–3, 1863, cast a long shadow—one that continues to shape discussions about war, memory, and the meaning of sacrifice in the American story.

Reference

National Park Service – Gettysburg National Military Park

https://www.nps.gov/